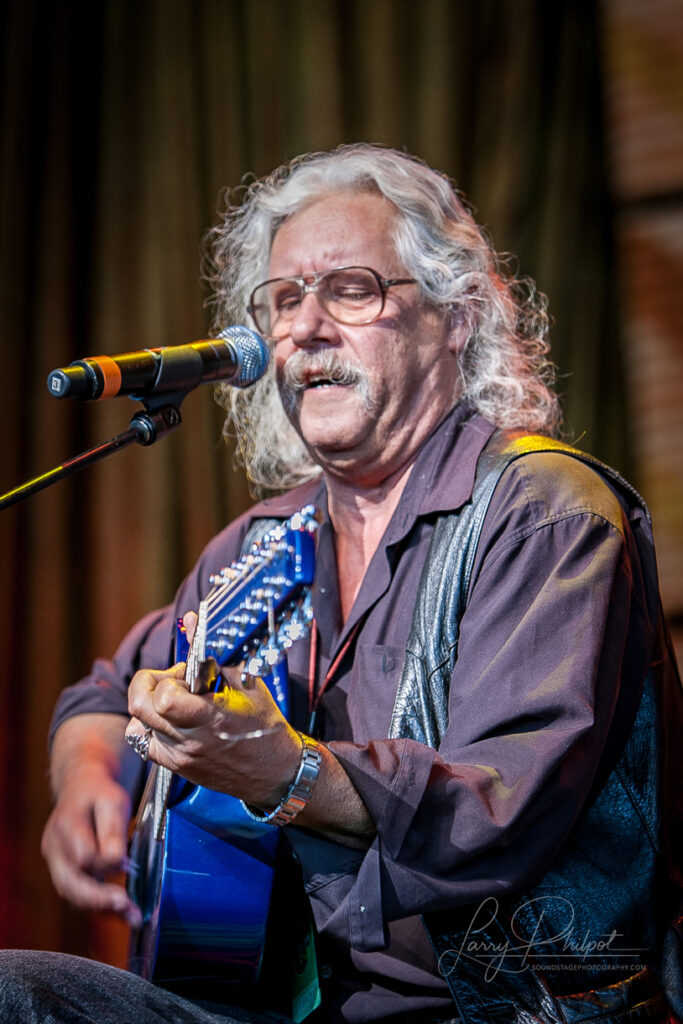

Arlo Guthrie: The Folk Scion Who Found His Own Voice

Imagine a boy in Brooklyn, 1947, watching his father strum a guitar through a haze of illness, the room thick with stories and songs older than the city itself. For Arlo Guthrie, music wasn’t just a career—it was a birthright, a thread woven into his DNA by Woody Guthrie, the Dust Bowl bard whose legacy loomed large. But what drove Arlo to pursue it? It wasn’t just his father’s shadow; it was the itch to tell his own tales, to take that folk inheritance and twist it with humor, heart, and a hippie’s defiance. Music became his way to honor the past while dodging its weight, a ramble through life that turned a kid with a famous name into a troubadour all his own.

From Coney Island to the Catskills

Arlo Davy Guthrie was born July 10, 1947, in Coney Island, Brooklyn, to Woody Guthrie and Marjorie Mazia, a Martha Graham dancer. The second of four kids—sisters Cathy (died 1947) and Nora, brother Joady—Arlo’s early years were chaotic. Woody’s Huntington’s disease cast a pall; by 1952, he was institutionalized, leaving Marjorie to raise the brood in Howard Beach, Queens. Arlo grew up on Woody’s tunes—“This Land Is Your Land” was a lullaby—but also on the Beatles and Bob Dylan, soaking in the ‘60s ferment.

School was spotty—Stockbridge School in Massachusetts kicked him out for mischief—but music stuck. At 13, he got his first guitar, a gift from Woody’s pal Pete Seeger. By 18, he was busking in Greenwich Village, his curly mop and sly grin winning over coffeehouse crowds. A stint at Rocky Mountain College in Montana ended quick—he dropped out to hitchhike, guitar in tow, chasing the folk circuit from coast to coast.

A Career of Rambles and Revelry

Arlo’s career kicked off with a 19-minute yarn: “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree,” debuted at Newport Folk Festival in 1967. Released on Alice’s Restaurant (1967), it made him a counterculture star—part song, part protest, all Arlo. He never led a band in the classic sense, but he’s rolled with crews. Early on, he gigged with Shenandoah, a loose collective featuring guitarist David Bromberg, bassist Tony Brown, and drummer Steve Cooley, backing him on Hobo’s Lullaby (1972) and beyond. His most consistent “band” was the road—pick-up players like fiddler John Pilla or pianist Terry A La Berry fleshing out tours.

Solo, he thrived—Running Down the Road (1969), Washington County (1970), Last of the Brooklyn Cowboys (1973)—mixing folk, blues, and wry wit. The ‘70s peaked with “The City of New Orleans,” a Steve Goodman cover that hit No. 18. After a ‘80s dip, he revived with Son of the Wind (1992) and kept rolling, often with family—daughter Sarah Lee Guthrie and son Abe Guthrie joined for Guthrie Family Rides Again tours. He’s collaborated with Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, and Pete Seeger, whose mentorship shaped him. Romances? Married to Jackie Hyde (1969-2012, her death) bore four kids; a 2021 marriage to Marti Ladd keeps it quiet.

On screen, he starred in Alice’s Restaurant (1969), directed by Arthur Penn, and guested on The Byrds of Paradise (1994). His tunes hit Two-Lane Blacktop and * Parenthood*. Awards? No Grammys, but Alice’s Restaurant went gold, and he nabbed a Grammy nod for Best Musical Album for Children (1997). The International Bluegrass Music Association honored him in 2016; no Hall of Fame yet, but Woody’s shadow counts.

Here’s a rundown of his biggest hits:

- “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” – Written by Arlo Guthrie, this 1967 epic hit No. 97, a Thanksgiving legend.

- “The City of New Orleans” – Penned by Steve Goodman, Arlo’s 1972 take reached No. 18.

- “Coming into Los Angeles” – Written by Arlo, this 1969 folk-rocker cracked the Top 100.

- “Massachusetts” – Crafted by Arlo, this 1976 ode became the state folk song in 2000.

Controversy on the Hippie Trail

Arlo’s dodged major scandals, but he’s stirred dust. His 1965 arrest for littering—dumping trash in Stockbridge—birthed “Alice’s Restaurant” and got him draft-deferred, a sly anti-war jab that riled hawks. In 2001, his buyout of the Trinity Church (Alice’s real-life spot) for the Guthrie Center irked locals who saw it as cashing in on lore. His 2020 retirement—post-stroke health woes—sparked fan dismay, though he’s hinted at comebacks. Politically, his lefty leanings—backing Occupy Wall Street, praising Bernie Sanders—have rankled red-state fans, but he shrugs it off with a grin.

A Night of Trash and Triumph: Newport, 1967

Let’s hop to July 16, 1967, at Newport Folk Festival—a muddy, 10,000-strong throng buzzing with Dylan’s electric fallout. Arlo, 19, was a wildcard, booked last-minute on Pete Seeger’s nudge. Armed with a battered Gibson, he ambled onstage, all curls and nerves, and unleashed “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree.” For 19 minutes, he spun the tale—Thanksgiving, trash, cops, draft boards—his voice a drawl, then a howl, the crowd cackling at “You can get anything you want!” Halfway through, a thunderstorm cracked—rain pelted the stage, mic fizzing. Arlo didn’t blink—yelled, “Sing it louder, folks!” and they did, a soggy choir drowning the deluge.

A string broke on “Group W bench”; he swapped guitars mid-line, quipping, “This one’s got all six, I hope!” By the end, soaked fans leapt fences to rush him—security waved ‘em through, Newport’s rules be damned. “I thought I’d bombed,” he told Rolling Stone later, “but they wouldn’t shut up.” Pete Seeger, backstage, hugged him: “Woody’s laughin’ somewhere.” The set—recorded, rushed to Reprise—launched him, a shaggy folk fable born in chaos. Fans still trade crackly tapes, calling it “The Rain Gig”—Arlo’s baptism by storm and story.

Arlo Guthrie’s journey is a folk odyssey—Woody’s heir turned prankster poet. From Brooklyn stoops to festival fields, he’s sung life’s absurdities with a wink and a strum. Catch a rerun of that Newport night, and you’ll hear a voice that’s weathered time, still rambling free.